Images of the Alchemical Laboratorium in the Medievalist World of The Witcher, Part 1

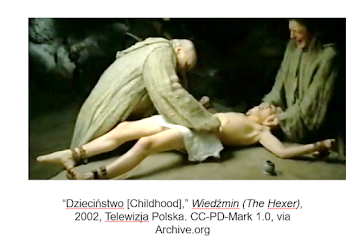

Like much of fantasy media (including the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin), the fictional world of Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher novels and short stories falls under the umbrella of medievalism. Medievalism is defined by Tison Pugh and Angela Jane Weisl (1) as works that “turn to the Middle Ages for their subject matter or inspiration, and in doing so, explicitly or implicitly, by comparison or by contrast, comment on the artist’s contemporary sociocultural milieu.” Common tropes in modern medievalist literature include the depiction of feudal kingdoms, pre-industrial technology and limited scientific knowledge, and widespread belief in superstitions (Ditomasso 151-2). Sapkowski’s universe has been adapted into a series of internationally successful computer games, a 13-episode Polish tv series Wiedźmin [The Hexer] in 2002, and the ongoing Netflix live-action adaptation The Witcher and animated prequel The Nightmare of the Wolf.

The science of the monster hunter – or witcher – Geralt’s world combines pre-Copernican science with technological aspects of the Industrial Revolution (what might be termed steampunk technology, in the expanded sense of any anachronistic technology used in popular culture, especially science fiction/fantasy). For example, dangerous and unethical genetic engineering plays a central role in the Witcherverse, including the creation of Witchers through mutating normal human children. This is accomplished through a scientific magic termed mutagenic alchemy, conducted by renegade sorcerers, the “mad scientists” of Sapkowski’s fictional world.

The term mutagenic alchemy brings to mind that of “genetic alchemy, or algeny” (Lederberg 521) coined by Nobel laureate biologist Joshua Lederberg. As described by Mary Midgley, “Just as the alchemists took all chemical substances to be fluid stages, engaged in becoming gold, and thought they could hasten that process, so (it is proposed) for the modern transmutator all life is a similar continuum, along which he can move any element at his pleasure” (Midgley 43). Jeremy Rifkin explains that “Algeny means to change the essence of a living thing by transforming it from one state to another; more specifically, the upgrading of existing organisms and the design of wholly new ones with the intent of ‘perfecting’ their performance” (Rifkin 17). Indeed, this precisely describes the goal of mutagenic alchemy in the Witcherverse, not only in the creation of Witchers but, most regretfully, the illegal manufacture of new forms of monsters for Witchers to hunt, thereby assuring their job security.

We now have the what and the how, but what about the where? In our modern world we stereotypically expect a scientist to work in a laboratory, an ominous space containing a dizzying array of strangely shaped glassware, open-flame Bunsen burners, bubbling multi-colored concoctions, pickled body parts in jars, and ominous sparking electrical machines. These stereotypical views are largely shaped by both distant memories of high school science experiments and Hollywood. As noted by the Tv Tropes website, the typical mad scientist lab features most of the following items, noting that “nothing shouts ‘science’ to the casual viewer more than a guy in a lab coat fiddling with a beaker of colored liquid” (TV Tropes). This trope probably owes much of its origin to the 1927 classic silent film Metropolis as well as 1931’s Frankenstein (TV Tropes).

Historically the laboratory as we commonly understand it is a modern invention. In the mid-15th century the Latin term laboratorium (from the root labor) referred to monastery workshops, analogous to the scriptorium (scribe’s copy room) copying room) and dormitorium (dormitory). By the 16th century, laboratorium referred to “workshops of alchemists, apothecaries and metallurgists, and subsequently came to refer to all accommodation in which natural phenomena and processes were explored by means of tools and instruments” (Schmidgen 4). These early labs were centered around a furnace, a design carried over into early chemistry labs. In the mid-19th century, the classic chemistry lab as we now know it came into popularity, featuring Bunsen burners and impressive collections of bottled chemicals (Morris 2021, 1).

The most iconic equipment of the alchemist’s laboratory (besides the furnace) was used for distillation. Gourd-shaped cucurbits were attached the beak of the connected alembic, allowing the heated material to vaporize in the latter and then condense in the former (Pyne).

Tools

included bellows, crucibles, and metal spoons, scissors, hammers, tweezers, and

files used with melted metals and various pots and vessels (often made of clay,

metal, and porcelain) used for distillation and other manipulation of liquids

(Ferrario).

Medieval woodcuts, engravings contain curious artistic representations of alchemical labs, often highly allegorical in style, as shown here. Some depictions were satirical in nature, reflecting prejudices against alchemy (Morris 2015, 23). Later paintings drew upon these less-than-accurate depictions, leading to further artistic exaggerations.

The 17th century Flemish painter David Teniers the Younger painted over 300 different representations of alchemical work, depictions that were problematic, as they were based on “genre paintings and still lifes” rather than actual laboratories (Pyne; Schmidgen 7).

The Alchemist, circa 1640s, David Teniers the Younger. Oil on panel. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig. CC-PD-Mark, via Wikimedia Commons

Putting together earlier depictions of alchemical labs with later representations, we can construct a list of “medieval” or alchemical lab tropes. You can easily spot most of them in this painting, for example.

Regardless of the lack of fidelity of many of these visual representations of the alchemical laboratory of the Middle Ages, they represent the source material available to any conscientious Hollywood set designer. Therefore, what would the medievalist version of these tropes look like in modern fantasy? I argue it is precisely the magical/scientific laboratories described in Andrzej Sapkowski’s medievalist world, as we will see using several examples.

In part 2, we will apply this analysis to images from various adaptations of The Witcher.

Comments

Post a Comment