Kosmos 482 and the Zombie Apocalypse

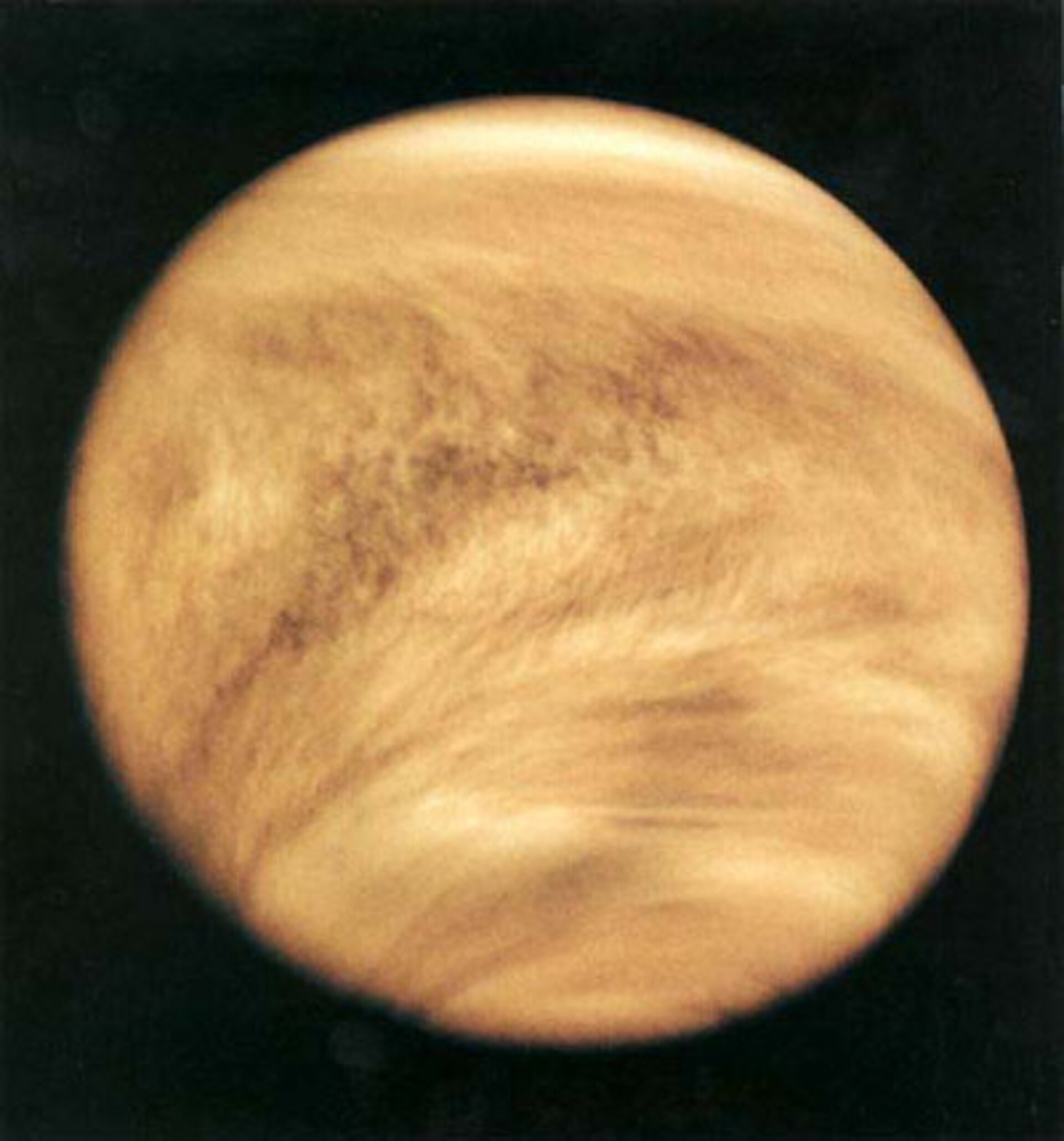

A May 16, 2002 article by satellite tracker and lecturer at Delft Technical University (Netherlands) Marco Langbroek explores the ultimate fate of Kosmos 482, a failed 1972 Russian space probe originally intended to land on Venus that instead got caught in earth orbit. Langbroek’s calculations suggest it will re-enter earth’s atmosphere “around 2025-2026.” Interestingly, since the probe was designed to survive what we now know to be the hellish conditions of the Cytherean atmosphere (with its clouds of sulfuric acid, temperature hot enough to melt lead, and pressures nearly equivalent to oceanic depths of a kilometer here on earth), it will probably survive the fiery descent, coming down somewhere between 52 degrees of latitude north or south of the equator.

Kosmos 482 is just one of a number of failed Venusian probes

launched by the Soviet space agency (and NASA) in the early decades of

interplanetary exploration. The first attempt to touch our nearest planetary

neighbor was launched by the Soviets on February 4, 1961, a modified Mars

exploration spacecraft intended to enter Venus’ atmosphere (an obvious sign

that at the time our understanding of the conditions of the Venusian atmosphere

were woefully inadequate!). Due to the failure of a transformer on the booster

rocket that had “not been designed to work in a vacuum” (doh!) the spacecraft “re-entered”

earth atmosphere three weeks later (Siddiqi 29).

Fellow Soviet vehicle Venera 1 (launched February 12, 1961) successfully

left earth orbit, only to lose contact with earth before its course-correction

motors could be fired; it is estimated to have passed no closer that 100,000 km

of Venus. The problem was later determined to be a “faulty optical sensor that

malfunctioned because of excess heat after the spacecraft’s thermal control

system failed” (Siddiqi 31).

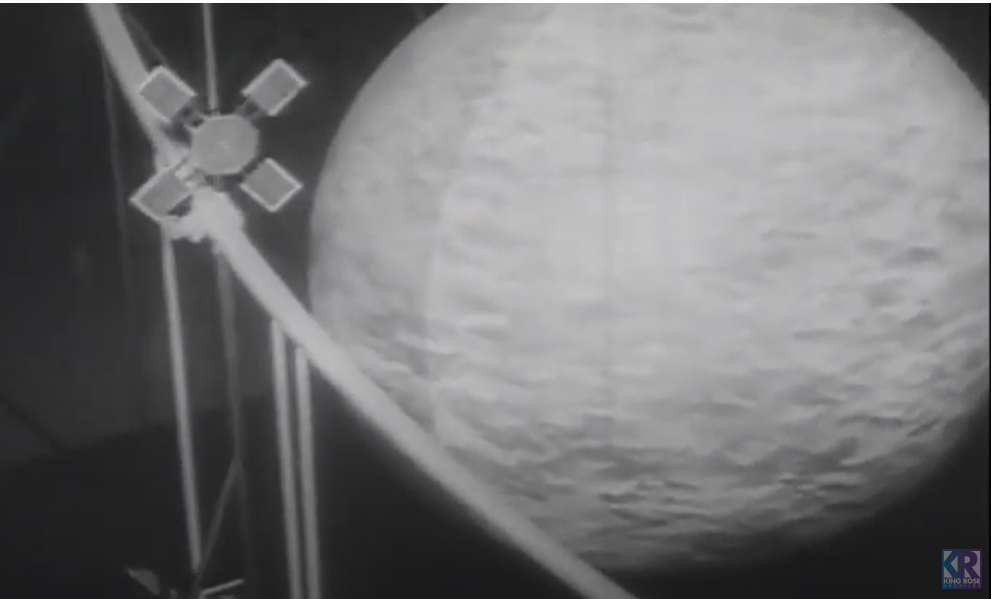

The first US attempt to fly by Venus also failed; on July 22,

1962 Mariner 1 failed to achieve the correct trajectory during launch and had

to be destroyed only 29 seconds later. Mariner 2, launched on August 27, 1962,

became the first successful interplanetary probe launched by humanity. On

J.R.R. Tolkien’s birthday, January 3, 1963, the probe passed within 35,000 km of

the Evening Star, sending back the startling information that our seemingly beautiful

sister world guarded several nasty secrets, including a dense layer of clouds

and a surface temperature of at least 800 F – so much for science fiction

writers who believed Venus to be a tropical paradise!

Three Soviet probes (two landers and one flyby) were launched

and failed in 1962, all three re-entering earth’s atmosphere within several days

of their launch. After licking their wounds, the Soviets tried again in

February and March 1964, the spacecraft once again failing to leave earth orbit

both times. A third probe, Zond 1, successfully left earth orbit in April, only

to suffer a series of hardware failures that rendered it unable to land on

Venus. While it flew by the planet at a disappointingly large distance of

110,000 km, it did send back publishable data on cosmic rays (high energy

particles in the interplanetary environment).

Venera 2 was not only successfully launched by the Soviets in

November 1965 but passed within about 24,000 km of Venus on February 27, 1966.

While it undoubtedly obtained valuable data, it was unable to share its discoveries

with its creators, as contact was lost with the craft before its scheduled data

relay (due to overheating of its solar panels). Venera 3 was launched only a

few days after its sibling, and was intended as a lander rather than a flyby. However,

communication was lost with this spacecraft as well, a few days before the probe

automatically separated and touched down, the first landing of a human-created

artifact on another planet. A third Soviet mission, launched the same month as

its siblings, failed to leave earth orbit and re-entered our atmosphere within a

month of launch.

Fast-forward to Venera 4, launched on June 12, 1967. This

probe successfully entered the atmosphere of Venus on October 18, 1967 – the first

probe to send back scientific data from the atmosphere of another world – but did

not survive the trip all the way down, succumbing to the extreme temperature

and pressure only 25 km above the surface. A US probe, Mariner 5, flew 4000 km

above the surface of Venus a day later. It confirmed the hellish nature of the

planet’s surface but failed to find evidence of charged particles trapped in a magnetic

field (an analogy to the Van Allen radiation belts surrounding earth). We now know that Venus does not generate its own intrinsic magnetic field (like earth

does) but instead has an induced field caused by the interaction with the solar

wind with the planet’s upper atmosphere.

The first successful landing on Venus occurred with Venera 7,

sending back 23 minutes of data from the surface on December 1970, while Venera

9 sent back photographs and 53 minutes of data from Hades I mean Venus on

October 22, 1975. Of course, there were a number of “oops” interspersed in between

these successes.

So why the morbid curiosity with failed Venusian probes

launched in the 1960s, besides the fact that most of them re-entered earth’s

atmosphere and burned up?

Between July 1967 and January 1968 George Romero filmed what

became one of the most iconic horror movies of all times, Night of the Living

Dead, in rural Butler County, Pennsylvania. As the film unfolds, the main

characters, trapped in the farmhouse, try to piece together what is causing the

epidemic of violence, hoping that the information will help them survive. The

discovery of a television in an upstairs bedroom offers the characters – and the

viewers – isolated bits of information, including a possible connection to the “recent

Explorer satellite shot to Venus” that “started back to earth but never got

here,” instead being “purposefully destroyed” after orbiting Venus when it was discovered

to be carrying a “mysterious high-level radiation.” A NASA scientist leaving a

meeting of the President’s cabinet offers that there is a “definite connection”

between the explosion of the probe and its “unusual amount of radiation” (which

he believes to be more than enough to cause significant mutations) and the

zombie outbreak, while a military leader disagrees.

Given the history of Venus exploration detailed above

(including the propensity of Venus-bound probes to re-enter earth’s atmosphere,

albeit long before encountering the second rock from the sun), it is not

surprising that Romero included this extraterrestrial explanation for the

zombie outbreak. The intentional inclusion of a strange “radiation” is even

more understandable given the timing of the film in the height of the Cold War

and the Space Race. As explained by Glenn Kay, zombie films of the 1950s and 1960s

openly drew upon societal anxieties concerning “atomic scares and alien menaces.”

Clearly a “mysterious high-level radiation” from space is the perfect storm in

this regard. But it wasn’t merely in fiction that such anxieties were stoked. A

1967 Universal Newsreel story from Jet Propulsion Laboratories in California

concerning Mariner 5 discussed the discoveries from Venus against suspenseful background

music reminiscent of any horror film. Among the claims is that Mariner “probed the

radioactivity of Venus, to determine the possibility of man landing there,” rather

sloppy reporting of the search for radiation belts around the planet described

above. As I described in a recent blog post, the public’s misconceptions about “radiation”

are well-known, and can be easily exploited by both Hollywood executives and newsroom

producers to fit their needs.

Regardless of Romero’s intention, his zombies are now counted among the archetype of what Margaret Twohy calls the “contamination zombie,” in which the animation of the dead is caused by some external agent (a parasite, a pathogen, or, as in the case of NotLD, radiation) infiltrating the body and contaminating it.

I therefore fully expect there to be some “tinfoil hat” claims regarding the supposed danger of Kosmos 482’s re-entry, certainly coming to an Internet near you. I offer all of this information so that you, too, can join the joyous game of pseudoscience whack-a-mole. Now if I could just remember – am I supposed to wear it shiny side in or shiny side out?

Kay, Glenn (2008) Zombie Movies: The Ultimate Guide.

Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

Siddiqi, Asif A. (2002). Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958-2000 (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History, No. 24. NASA History Office.

Comments

Post a Comment